A full generation before anyone coined the concept of “toxic masculinity,” there was John Singleton’s Boyz n the Hood. Yes, I could write about how Boyz n the Hood illustrates the realities of gang violence as this film is part of the Black Pantheon because the scene where Tre (Cuba Gooding Jr.) yells “RICKY!” in the infamous drive-by shooting of Morris Chestnut’s character is so indelibly etched into our collective consciousness. However, I am more interested—fascinated, in fact—by Singleton’s depiction of how Black life flourishes despite the circumstances of violence not necessarily through alcohol, guns, and drugs, but capitalism.

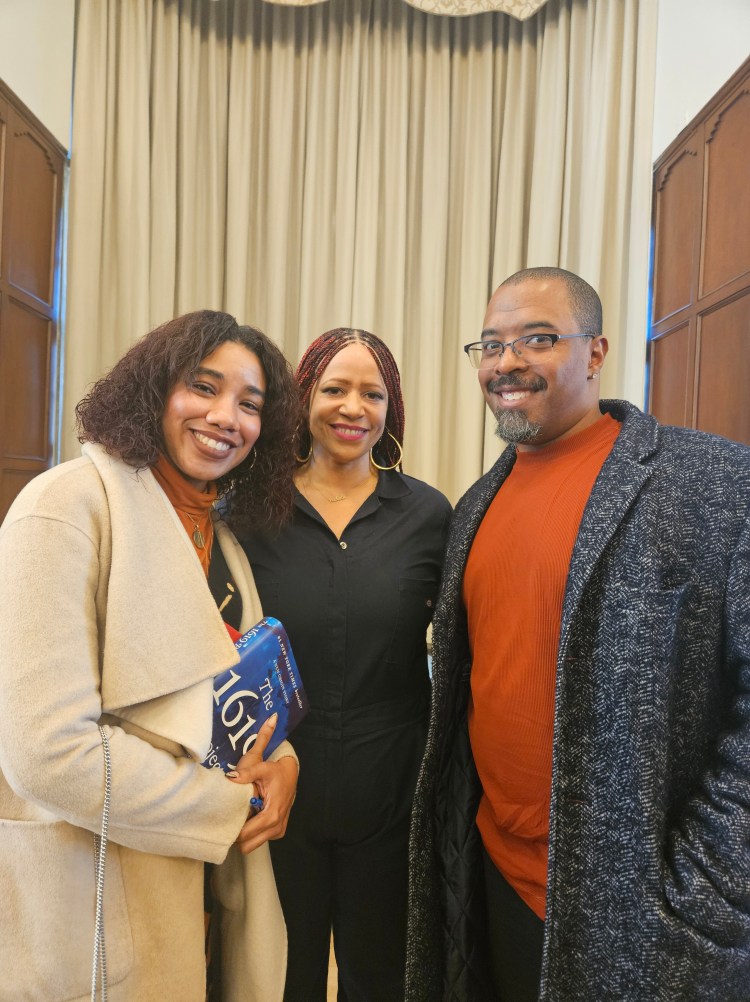

The meat of Nikole Hannah-Jones’ 1619 Project remains an ambition for my Git Lit column. For now, I attended a talk Nikole Hannah-Jones delivered at the University of Michigan where she stated that white supremacy and capitalism were inextricable. The United States forged the cornerstone of its wealth with the purloined, forced labor of black bodies in the fields, a fact that the Confederacy knew intimately to the degree that it could survive secession as an independent nation of states. The zero-sum game of exploiting (Black!) bodies so that white bodies may benefit is fundamental to how the United States has historically operated; capitalism and racism are analogous.

While gang violence masquerades as the forefront of Boyz n the Hood, Singleton’s film demands that audiences interrogate their understanding of what “gang violence” entails. Cinema aficionados romanticize films like The Godfather, Goodfellas, and Scarface, yet the demographics of these coalitions lack Black people. While Boyz n the Hood precedes New Jack City by a few months, the tandem of Singleton and director Mario Van Peebles’ projects would indict the racial stratification of the gangster film genre. When it comes to crime syndicates, white privilege enables the romanticization of “mafias,” while Blackness permits disparaging of “gangs.”

But what is a gang but a group, a collective, a cohort? The residents of South Central LA find solace in the camaraderie of their oppression rather than buy into the myth of rugged individuals pulling themselves up by their bootstraps. Capitalism hates when the marginalized disengage from participation through improvisation.

In fact, Singleton’s vision for the astute entails providing a counter-narrative to anti-Black propaganda, such as Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s 1965 The Negro Family: The Case For National Action, which was still in the discourse during the Reagan and H. W. Bush administrations. So while the Moynihan Report concerns itself with “black pathologies,” such as “matriarchal” family structures, Boyz n the Hood depicts in 1991 how non-traditional family structures could work before they became socially acceptable.

A young Tre (Desi Arnez Hines II as a child; Cuba Gooding Jr as an adult) gets into a fight at school, and his single mother Reva (Angela Bassett) decides that her son should move in with his father, Furious (Laurence Fishburne). Singleton juxtaposes this simple plot element against anti-Black propaganda suggested that absentee Black fathers and a prevalence of single Black mothers contributed to Black poverty, Black crime. As Toni Morrison once famously said, “The true function of racism is distraction”:

It’s important, therefore, to know who the real enemy is, and to know the function, the very serious function of racism, which is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining over and over again, your reason for being. Somebody says you have no language and so you spend 20 years proving that you do. Somebody says your head isn’t shaped properly so you have scientists working on the fact that it is. Somebody says that you have no art so you dredge that up. Somebody says that you have no kingdoms and so you dredge that up. None of that is necessary. There will always be one more thing.

The precience of Furious and Reva’s co-parenting arrangement would be vindicated two decades later, when the CDC would provide data proving that Black men are more involved with their children’s lives than any other racial group. Of course, this does not happen without conflict—often in real life, and certainty not in the movie. Furious and Reva argue about the direction Tre’s life should take, a subject that likely provoked his parent’s breakup despite their residual feelings that are more than just Bassett and Fishburne’s on-screen allure.

Pause. First of all, I never noticed that friggin Angela Bassett was in a “hood” movie. That’s crazy. Fishburne himself had to have been a hot commodity, too, from School Daze to this! It’s clear that casting director Ruben Cannon recognized Bassett and Fishburne’s chemistry, as they were Tina Turner and Ike in What’s Love Got to Do with It (1993).

Unpause. It is important to recognize that Singleton does not portray Bassett as the nighmare of the conservative’s worst imagination: the welfare queen. When Tre’s teacher calls Reva to inform her of his suspension, she begins to speculate about the condition of Tre’s home life. Reva rebukes the probing questions, pointing out that she is employed and working on her master’s degree. The teacher is perplexed when Reva says that Tre is going to live with his father instead of returning to the same school, and punctuates the conversation with “Yes, his father! Or did you think that we made babies by ourselves!?”

Yeah, you tell ’em Angela! Years later, she calls Furious to check in on Tre, and Singleton shows the audience that she has indeed finished her master’s via the decor of her upgraded house—a fantastic example of “show, don’t tell.” Singleton is also prescient here: we now know that Black women are the most educated demographic in the United States.

One should expect that with a title, Boyz n the Hood, Singleton should offer a commentary on Black masculinity. I will simply point out the obvious: the presence of Tre’s father as an influence is the difference between Tre joining Doughboy (Ice Cube) for a revenge gang killing, and not becoming involved with murder. Tre matriculates Morehouse while Doughboy dies weeks later off-screen.

So if black men are more involved with their children than other racial groups, where are the other “boyz” fathers? Well, this is where Officer Coffey comes in, representing the Repressive State Apparatus. The shadow of extrajudicial police behavior such as racial profiling looms in the scene when Coffey pulls Tre over and puts his revolver on his face for reasons the film does not state explicitly. Powerless, Tre retreats to his girlfriend, Brandi, (Nia Long) and trauma dumps in an impotently somatic, but tearful outburst (which she finds attractive enough to let him hit for the first time—fellas take note that “crying in front of a female” is attractive to women). In other words, if the cycle of violence does not claim the Rickys of the world, the Prison Industrial Complex needs its docile Black Bodies.

The Wire depicts the evil of capitalism-as-inextricable-from-white-supremacy better than any other media to date. To summerize briefly: capitalism creates the illusion of scarcity on the streets, on the docks, in the schools, in the political sphere where decisions are made—dare I say “the room where it happens”; companies pay hundreds of millions upfront for machines to do the work that stevedores can do more effectively and cost-efficiently, but the acquisition of machines is not for efficiency, but to give the local union the middle finger because how dare they demand fair wages! Schools are trash, and serve as much as daycare as educational institutions, their funding to do real work limited because the police threaten to go on strike if they don’t get raises. And yes, Hamsterdam is a highly fictional yet theoretical example of how Defunding the Police could work. There enlies the contradiction again—as with mafias versus gangs, those minding their business in rural communities enjoy the kinds of liberties that those condensed within cities do not. Thus, the Repressive State demands sthose docile Black bodies for cheap labor to fight wildfires and whatnot.

Slavery by another Name. Capitalism. Whatever. The gentrification that Furious discusses, and so on. Boyz n the Hood might contain violent scenes, but Singleton shows how we thrive despite the unacknowledged violence committed against Black communities daily.

Singleton addresses some of the unfortunate self-inflicted wounds, too. Not just Doubhgoy’s friend who did not know he could contract HIV from oral sex—clever sex ed insert by Singleton by the way—but it’s also unfortunate that Doughboy would only pick up books while he was in prison. Sounds like he was quoting womanist literature, suggesting that if women were in power, the world would be less violent.

As the US has rejected another woman candidate who was more credentialed than her opponent, one can still dream. One can still hope. Just not the Obama kind of hope as we’ve crossed beyond the Rubicon….