*SPOILERS*

My initial impression after watching the trailer for The Blackening for the first time is that this would be a movie where all the black people survive because they are determined to not do the things that white people do in horror movies, such as investigate suspicious noises, split up, distrust friends who are trying to help, fall due to a lack of athleticism when the killer is in pursuit, clumsily drop critical survival items at a crucial time, and fail to make sure the killer is deader than dead. It is as if The Blackening aimed to release when The Black Guy Dies First: Black Horror Cinema from Fodder to Oscar was published February 2023, de-centering the trope of white (women) requiring protection due to their fragility. This de-centering also manifests with its black director, black writing team, and an all-black cast. Finally, we get a horror movie where we are not mere spectators but participants by proxy.

Among the cast, character tropes endure, but on our terms. Lisa (Antoinette Robertson) is the über successful professional who makes dubious choices in her personal life. Dewayne (Dewayne Perkins) serves as both Lisa’s best friend and the token gay man of the group, persistently side-eyeing her for renewing her “friendship” with an ex who previously had been unfaithful. Nnamdi (Sinqua Walls) is the tall, dark, and handsome ex—the kind of good-looking such that the women in the audience would empathize with Lisa’s taste for men. Rounding out this clique is the biracial Allison (Grace Byers), who vacillates in her identity when the punchline requires her to do so.

The reformed gangsta, now married to a snowbunny, King (Melvin Gregg), arrives at the wood cabin before everyone else, and the five-O are profiling him before he can even get on the screen. Lagging behind are Shanika (X Mayo), the party girl who is into street pharmacology, and Clifton (Jermaine Fowler), the nerd whose name no one can remember—a 21st-century interpretation of Steve Urkel, complete with bizarre facial expressions when speaking and social awkwardness. A game of Spades breaks out and no one trusts him enough to play. I will return to this.

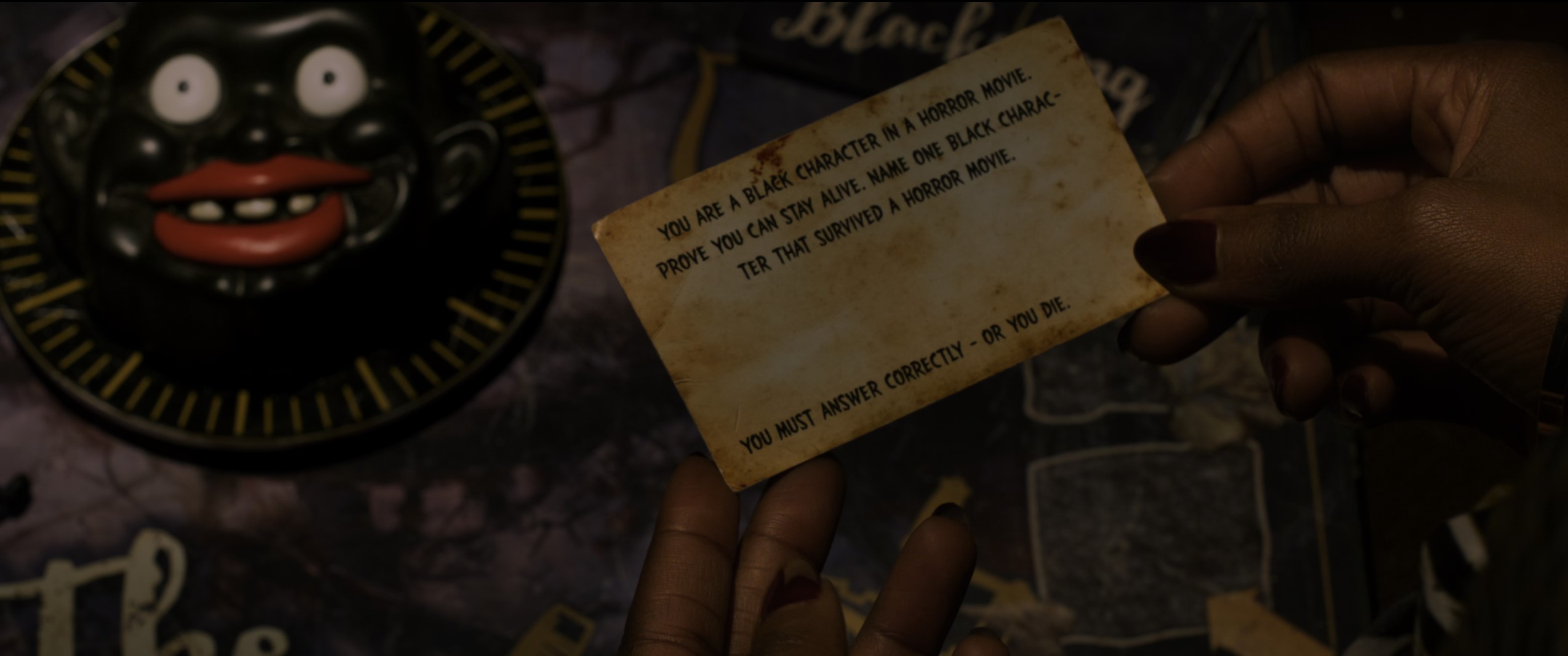

This cast of archetypes facilitates conventional horror tropes. The power goes out, and the only illuminated room in the house is the “game room,” the chamber in which two characters succumb during the film’s introduction. Dramatic irony ensues as the dramatis personae engage with the titular board game. Indeed, The Blackening revolves around a board game! Jigsaw rolls over in his grave as the console television cuts on to show a tar baby matching the Sambo figure on the cover of the board game. In order to live, the game threatens, everyone has to play; the gang has to answer questions ranging from what the second stanza of the Black National Anthem is to how many seasons before the dark-skinned Aunt Viv was replaced on The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

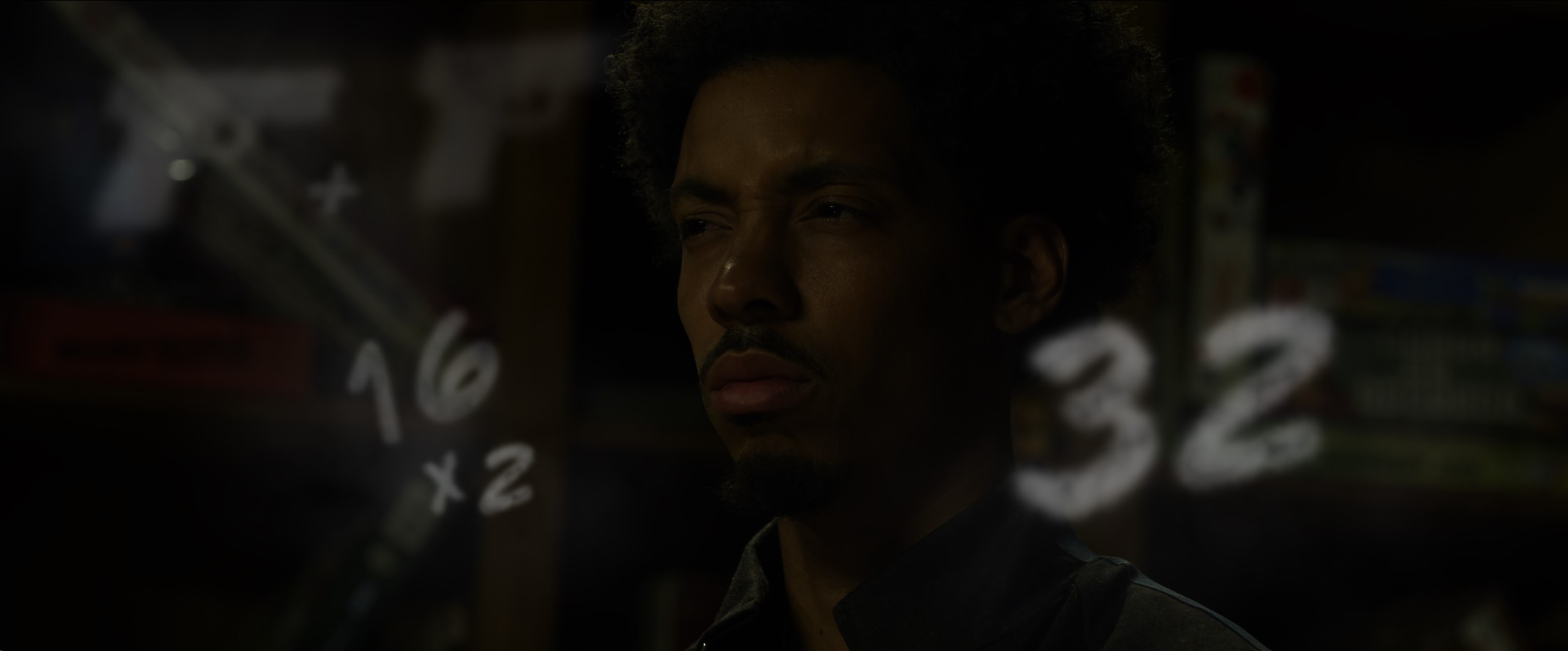

In the Tyler Perry tradition of drama, Clifton would be characterized as the lame yet stable brotha who the main love interest ignores until she comes to her senses during the plot’s climax. As The Blackening is something of a parody like Scary Movie, the film attempts to subvert established conventions, though Lisa and Nnamdi consummate their…friendship…off-screen without consequence, and the film unceremoniously absconds with that story thread. Under duress, King turns gangsta, Sanika provides stimulants that give Allison powers, and when the game asks them to sacrifice the blackest among them, Clifton is sacrificed even after admitting that he has never seen Friday, thought that Black Twitter was a seasoning, enjoys Jimmy Fallon without The Roots, felt threatened by Beyonce’s Super Bowl Performance, and voted for Trump twice. Here is where we get into real spoiler territory.

Because The Blackening is a parody, I do not think that anything of value was lost when I surmised that Clifton was the mastermind behind the activities in the hostile house practically as soon as he is introduced; after all, a blackfaced killer shoots him with a crossbow and drags his body off-screen, as opposed to leaving his corpse as bait or getting dismembered as is common in horror movies. When the characters eventually end up in a room where Clifton’s cadaver awaits, he revives to reveal that after reneging during a Spades session ten years ago, this group of friends revoked his “black card,” and the associated shame drove him to inebriation to the point of intoxication and he subsequently he kills a woman while behind the wheel. After serving four years in prison, he plots his revenge against the party.

I find this reveal, this outcome, discouraging. As media catering to black audiences becomes increasingly progressive, I feel that making the nerd who enjoys playing board and card games ( albeit poorly) the bad guy regresses modern expressions of black identity. I only come to Clifton’s defense as I relate to him the most out of any other character in The Blackening as an often socially awkward introvert who does not dance like Dewayne or makes jokes like Shanika, or takes recreational drugs like Allison, or would be perceived as cool like King or Nnamdi. After all, I named this blog “Blerd Beats” because I identify as a black nerd, which has been trending as a respected identity over the past 10-15 years with the emergent popularity of the MCU, anime (beyond Naruto, DB [Z; Super], and Bleach) cosplay, and of course video games outside of Madden and NBA 2K.

While The Blackening is entertaining, I certainly hope that viewers do not walk away believing that blackness is a concrete, static thing, accessible exclusively via performative paradigms. Granted, I write this in defense of Clifton’s nerdiness. The negroes (because The Blackening is not shy of calling them the other word) who engage in politics contrary to the black community’s interests, and therefore their own, out of misplaced spite? Well, Samuel L. Jackson said it best: