Back in 2020, I dedicated myself to reading more—one non-fiction and one fiction book per month, alternating between fantasy (where possible) and sci-fi for the latter. While reading Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements and considering it for review, I realized that despite being a huge fan of Octavia Butler’s work, which has contributed significantly to my taste profile for speculative fiction, I have yet to write on any of her work. Fortuitously, Damian Duffy adapted Kindred into a graphic novel in 2017.

Kindred is widely considered to be Octavia Butler’s most famous work, appealing to audiences of both historical fiction and speculative fiction. In this way, Duffy’s Kindred: A Graphic Novel Adaptation is meta, existing through the double medium of literary and visual art. Duffy similarly flakes at providing a reason why Kindred needed a graphic novel adaptation just as Butler eschews explaining how the main character, Dana, teleports through time and space.

Butler’s explorations of the past inspired my my own. I augmented my familiarity with the genre beyond the seminal Fredrick Douglass, Harriet Jacobs, and Solomon Northup (I am obligated to mention Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery as a Tuskegee alumnus). I read William Wells Brown’s Clotel; or, The President’s Daughter: A Narrative of Slave Life in the United States (1853), Harriet E. Wilson’s Our Nig: Sketches from the Life of a Free Black (1859), and Hannah Bond’s The Bondwoman’s Narrative (unpublished, discovered in 2002; written before 1860), but those are all 19th century works published with the intention of generating sympathy for the plight of African Americans in captivity. Prior to my exposure to Butler’s Kindred in 2008-2009, I had not even known that a genre dedicated to modern slave novels existed, let alone that I would find them so enrapturing: Shirley Anne Williams’ Dessa Rose, Margaret Walker’s Jubilee, and Ishmael Reed’s Flight to Canada are examples of Kindred’s peers; they would be among the first novels in the 20th century to put the “neo” in “neo-slave narrative.”

Kindred begins in what would have been the present at the time Butler was writing—1976 in the novel, against its 1979 publication date. Not even a full decade after the Loving v. Virginia ruling, Butler dares to portray an interracial marriage between Dana Franklin and her husband Kevin. Dana’s sudden disappearance disrupts their short-lived introduction as a recently-married couple. She regains consciousness near a river where a boy is drowning, and would be reasonably expected from individuals with the ability, she dives in to save him. From the shore, a distressed woman his name, “Rufus!” Dana swims Rufus over to her, and she is thanked not with a hug, but with fists. As a rifle barrel thrusts itself into Dana’s face from beyond the panel, she teleports back into her own timeline.

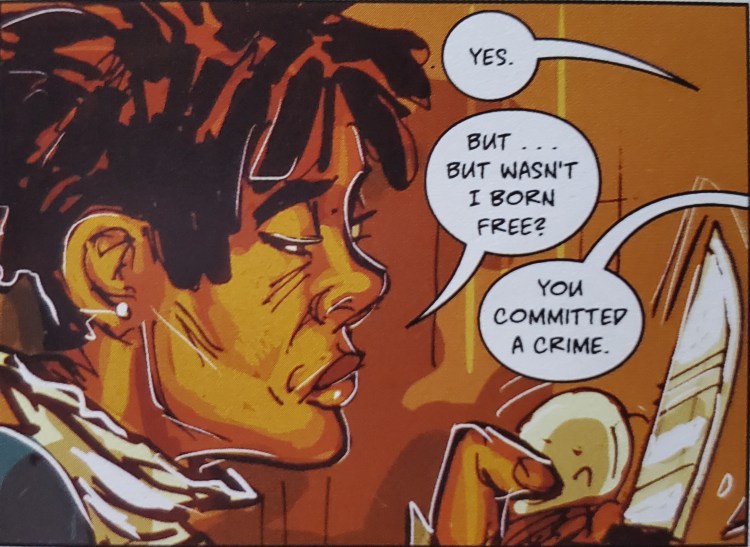

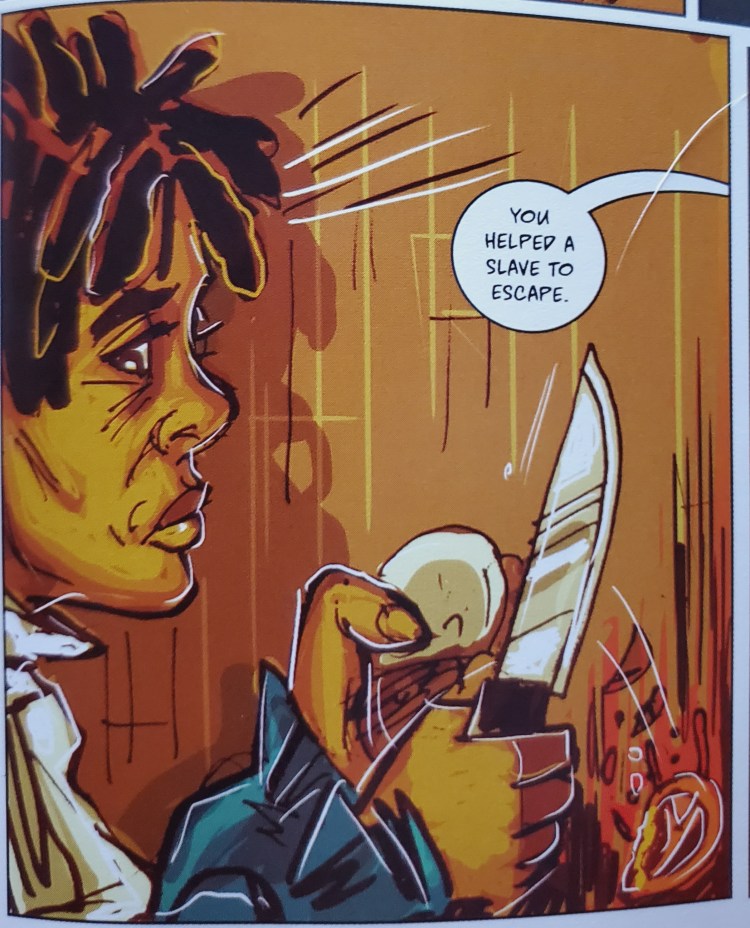

Over time, Dana would get recalled back into the past again and again, each event triggered in time to save Rufus from a series of foolish decisions. During her second trip, after preventing Rufus from burning down the Weyln Plantation, she recalls the crucial detail that the name of her grandmother Hagar Weylin, and realizes that Rufus Weylin and Alice [Greenwood] are her great-grandparents—Rufus would grow up to become the plantation master, and Alice his slave concubine. Though black people generally assume that a white male can be found within their patrilineage because of rape, the revelation that Rufus is her direct ancestor comes to Dana as a grievous shock, especially because even though she keeps getting pulled to the past, each time he is sent back to the present after experiencing a brutal trauma that only slavery could inflict.

One of the aspects that makes Kindred a novel that is worthy of discussion to this day is Dana’s interiority in light of this new information. Because she barely survives a brutal beatdown and rape attempt as the result of mistaken identity, readers might expect Dana to save her great great great grandmother from similar horrors. This hypothetical Dana might travel north and become an agent active within the inner workings of the Underground Railroad like Cora in Colson Whitehead’s novel of the same name. This imaginary Dana, being literate, pens letters and works that would be placed alongside the abolitionist efforts of Frederick Douglass, Harriet Jacobs, and William Wells Brown, etc, to kick off the Civil War. Dana, then, would be viewed as a modernized historical fiction folk hero.

Instead, she upholds the status quo.

Kindred is considered a speculative novel primarily because Butler intentionally obfuscates the cause for Dana’s spontaneous time travel. Only a near-death experience for Rufus or an equally excruciating situation for Dana triggers her transitions. In either circumstances, one fact remains consistent: Dana is vested principally in her own self-preservation. Her sole focus during these excursions in nineteenth-century Maryland is to ensure that Alice bears her daughter, Hagar, from whom she can trace her matrilineage to the present. This translates into Dana personally grooming Alice for Rufus, effectively doubling the impact of her bodily autonomy being forfeit. Coercion is not consent.

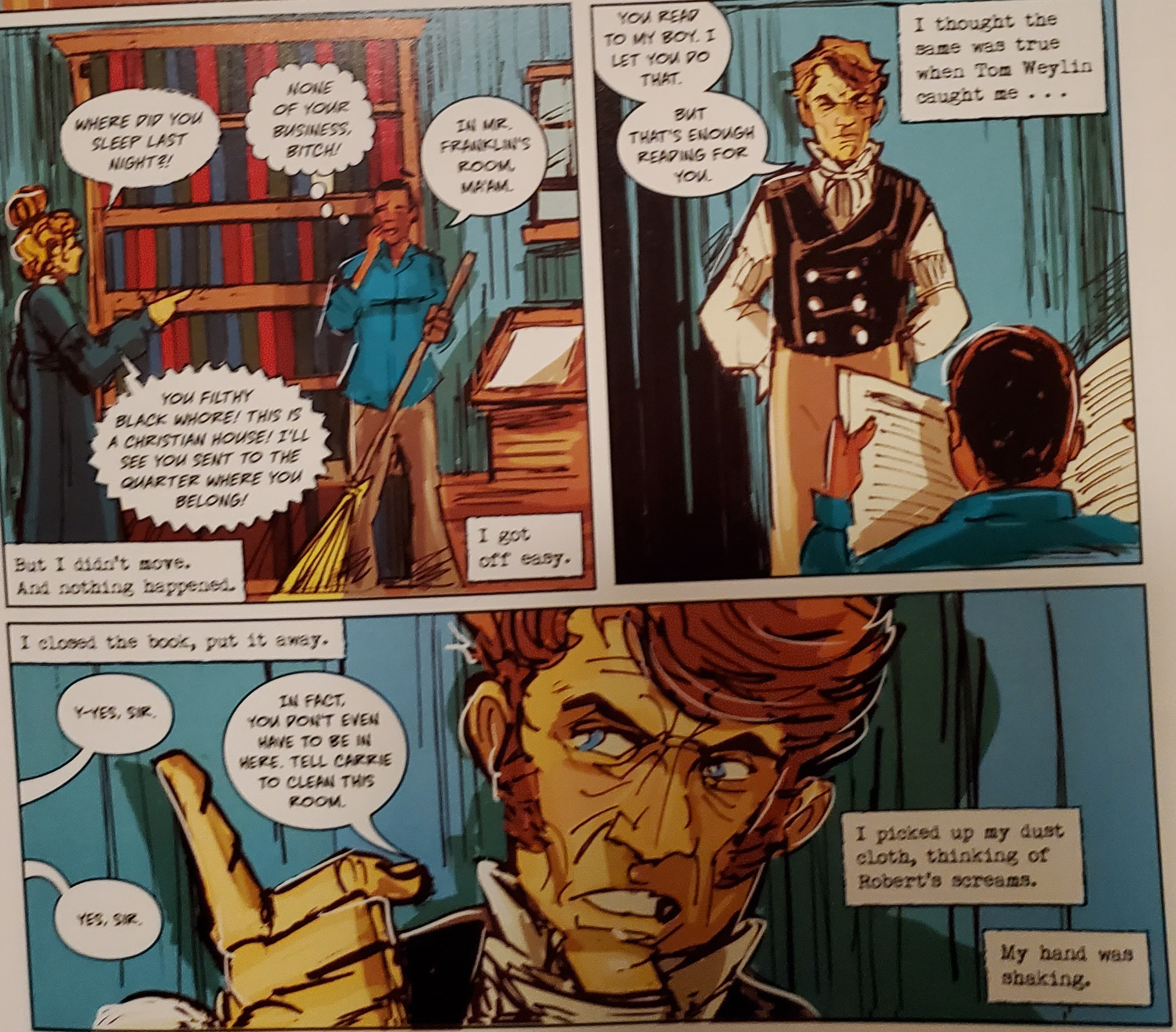

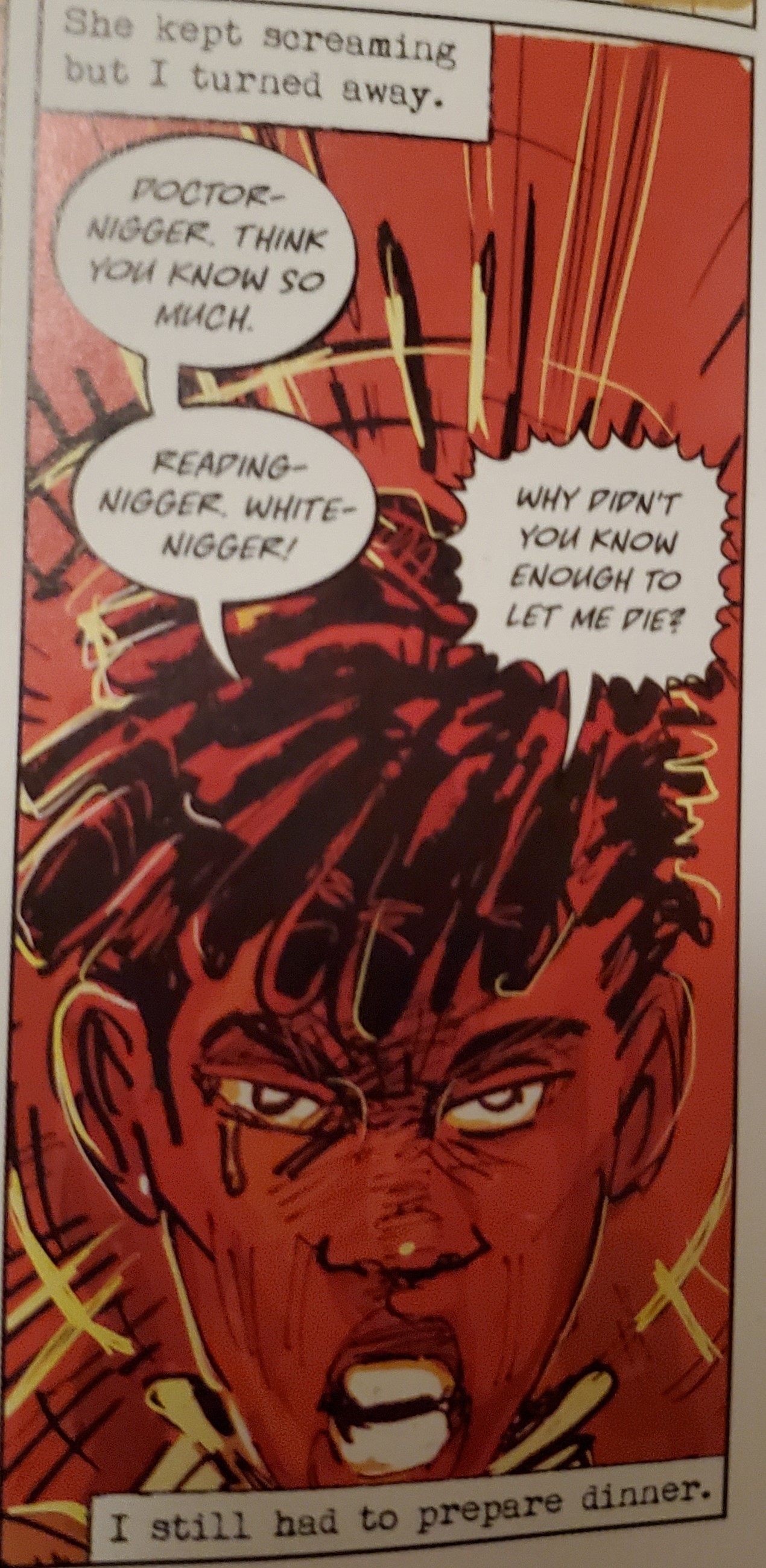

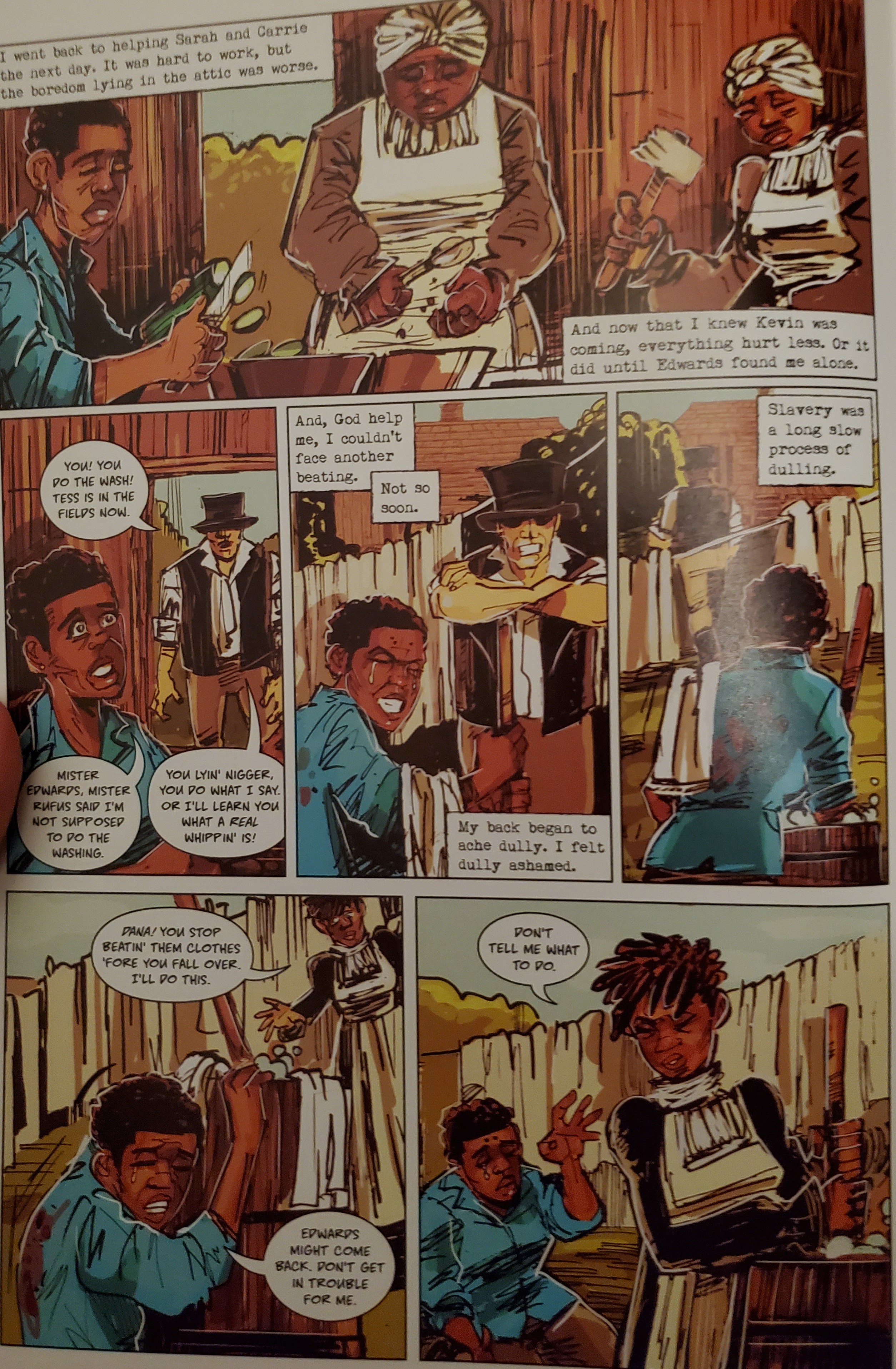

Butler flirts with these complexities of the peculiar institution, such as this volatile love-(mostly) hate relationship between slave and master. While Dana has mammy-like influence over a Rufus in his adolescence, she tries to teach him to be the best version a white plantation owner could possibly be. For example, he stops calling her the N-word upon her request.

Rufus seems like he will mellow out and become a better man than his unscrupulous father, and yet his vindictiveness demonstrates his potential for cruelty. Rufus tries to rape Alice, and her husband Isaac beats him to an inch of his life. Dana nourishes Rufus back to health, and in return, he almost immediately arranges for Isaac to be sold downriver, and buys Alice for himself. Naturally, Alice hates Dana because how she seemingly prioritizes Rufus’ well-being over that of any slave.

In a strange twist that I struggled with for a decade after reading it for the first time, there comes a point where Alice and Rufus appear to be content with each other. This intrigued me, because everything I knew about slavery taught me that no slave could ever become content while in bondage. However, Sarah the cook explains how she tolerates her circumstances because her fourth child, Carrie, is the only child Weylin did not sell; she has a reason to endure and not poison the food.

This is something that Rufus forgets when he fully embraces his role as plantation master. He sells off his own children, because in his eyes, they are property rather than people. Only after Alice takes her own life does Kindred proceed as readers might expect. Rufus then begins to view Dana as prey, and she finds the strength to defend her honor, making the choice that readers like myself believe she should have made all along.

In this way, Kindred presents to readers many difficult ideas to swallow. Had Dana allowed Rufus to die, everyone would have been sold off in an auction as inevitably indicated in the epilogue. Had the slaves tried to escape, patterrollers would have apprehended and crudely mistreated them, like what happened during Dana’s first encounter with Isaac and Alice. Even when Dana’s white husband, Kevin, joins her during one of her trips, he can’t save her from receiving a lashing of her own. Thus, there is no escape from the Peculiar Institution—Dana’s missing arm illustrates that there is a cost to forgetting and a price for remembering this dreadful history.

I do think that kindred is easier to consume as a graphic novel then as a straight Textual one. Of course, hats off to Damien Duffy for what I believe to be an impressively thorough maintenance of Butler’s original intent.

I am not particularly fond of the John Jennings’ art style esthetics though, particularly Dana’s depiction. I feel like Jennings deigned to draw Dana in the likeness Butler herself. When Dana goes back into time, characters comment about her wearing trousers like a man. I think Jennings takes this literally, depicting Dana with a Caesar-style haircut, making her appear on-page as androgynous. A positive interpretation of this choice would be to think about how if Dana were actually male, she would be no more safe during slaver. In fact, one could say that slaves and masters alike are relieved to know that she is a woman who knows her place, rather than a dangerously uppity buck negro. Still, I would have preferred Dana to sport locks, and Alice the shorter hair.

Jennings is as shrewd with the violence as could be considered possible in portraying chattel slavery. Thankfully, Dana’s inexplicable ability to escape the worst of her punishments for daring to bring modernity to the past spares both herself and the reader the worst of it. Without a doubt, Kindred is an enthralling novel in its literary or graphic form.

One thought on “Comix Zone—Kindred: A Graphic Novel Adaptation”